Chief Justice earns the title with his decision on Obamacare

With most titles of great power and authority, such as President, Queen, or in this case, Chief Justice, two things have to happen before the position is fully owned and deserved. The person must be elected, appointed or as is often the case with royalty, just be born. Then comes earning the position and the moral authority that goes with it.

John Roberts, appointed to the Supreme Court in 2005 by President George W. Bush, truly became Chief Justice on June 25, 2012, with the decision and his tie-breaking and virtually solitary opinion upholding almost the entirety of the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare.

Critically, Roberts’ opinion upheld the so-called “individual mandate” in the law, a provision that requires almost all Americans to have or acquire health insurance and failing to do that pay a tax penalty to the IRS.

I’ve thought since reviewing the extended oral arguments in this landmark case that Chief Justice Roberts, not Justice Anthony Kennedy as widely expected, would be the determinative vote. (See “Watch Out for Kennedy,” Times Union, April 30, 2012).

I disagree with most of the reasoning employed in Roberts’ opinion. That doesn’t matter. Nor does it matter that four liberal Supreme Court justices, led by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and four ideologically conservative justices, led by Antonin Scalia, wrote 127 pages disagreeing with his reasoning and at times belittling him with nasty and puerile rhetoric.

Roberts understood this crucial moment in history and accepted his responsibility to move the nation forward. In so doing, he truly became Chief Justice of the United States.

Chief Justice Roberts’ opinion first held that a challenge to Obamacare was ripe for determination, despite the fact that the mandate imposed a tax not yet collected, and arguably not properly challenged unless the tax was already paid and a refund sought.

Second, Roberts rejected the first two constitutional justifications for the mandate asserted by the Obama administration’s Department of Justice. He said it was neither a proper exercise of the federal government’s power to regulate interstate commerce nor a “necessary and proper” adjunct of government authority to administer the balance of the clearly constitutional Obamacare legislation.

The Commerce Clause analysis is crucial to understanding why this decision will have to be reckoned with further as the limits of federal authority and the boundaries between state and federal power are determined by future jurists.

The Commerce Clause gives the federal government authority to regulate a national economy and ended the chaos that reigned when 13 loosely joined states favored their own commercial interests. However, as time went by, the courts interpreted the commerce power more and more broadly.

The high- or low-water mark in prior Supreme Court decisions occurred in the case of Wickard vs. Filburn. The Supreme Court upheld a federal law that prevented an Ohio farmer from growing wheat for his own home consumption, because that grain might eventually seep into the interstate market or might prevent the farmer from having to buy wheat for his own consumption in that market.

Chief Justice Roberts essentially said enough is enough, and that the commerce power could not be used to justify everything the federal government wanted to do, regardless of how noble the goal was. I believe that Roberts’ reasoning misconstrues prior precedent, but clearly he is saying that those decisions are wrong and that he is the Chief now.

Robert’s rejection of the necessary and proper justification is similar, again saying that first the Constitution must give the government the authority to do something. Failing that, while the mandate might be “necessary” for Obamacare to work efficiently, it was not constitutionally proper.

In sustaining the mandate as a tax, the Chief went beyond labels, slogans, rhetoric and the first part of his own opinion to find a way to do what a court is supposed to do — avoid substituting the will of unelected federal judges for that of elected legislators.

Sweeping aside all the times when President Barack Obama and members of Congress declared that the mandate was not a tax, the chief said that it was just that. It was a sum of money paid to the IRS under specified circumstances along with a person’s annual federal tax return. He owned up to the inconsistency with the part of his opinion holding that the mandate was not a tax for purposes of construing the Anti-Injunction Act, the law that prohibits challenging a tax before it has been paid.

Most important of all, the Chief gave his fellow grumbling Supreme Court justices, state governments and all of us voters a lesson in the Constitution and our own responsibilities under it.

To the court’s conservatives, of which he is clearly one, he essentially said it is hypocritical to call ourselves “strict constructionists” if we substitute our own view of what is wise for the will of the people, manifested by elected legislators.

To the liberals, he said, I know you want the commerce clause to justify anything the federal government wants to do, but you can’t always get what you want. This time you get what you need. This law, which I dislike, is nonetheless upheld.

To the states that challenged the law and have been allowed to say “no” to the part of Obamacare that vastly expands Medicaid, Roberts explicitly said, “the states are separate and independent sovereigns, sometimes they have to act like it.”

Here the Chief was pointedly telling states like Wisconsin, Ohio and Indiana, run by Tea Party-oriented governors and legislatures, that they could refuse all the federal money available to expand Medicaid to cover two to three times as many people as it currently does — but then get ready for the wrath of voters who are denied what’s essentially free health insurance. The Chief reminds all of us that we elected the President and Congress that enacted Obamacare, by saying, “It is not for us to protect people from the consequences of their political choices.”

In November, people will decide whether they like the choices they made in 2008 and 2010 in some measure by making the elections for president and Congress a referendum on Obamacare.

But before that, I cast a vote of gratitude to a judge with whom I generally disagree, but who has shown that he is a real and worthy Chief.

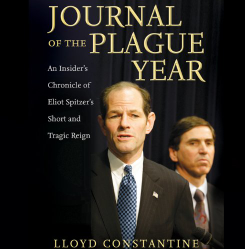

Lloyd Constantine is a Manhattan lawyer. He has argued before the Supreme Court and testified in the Senate’s Supreme Court nomination hearings.

0 Comments