New York City’s next mayor, Bill de Blasio, and his wife, Chirlane McCray, deserve credit for candor. Just as when Bill Clinton told the nation in 1992 it would “get two for the price of one,” de Blasio and McCray have openly declared their interchangeability.

In an interview in The New York Times, McCray revealed that she interviews all prospective high-level appointees and edits key speeches, and that policy meetings are planned around her schedule. Without apparent wink or giggle, McCray recounted that she threatened divorce if de Blasio voted to elect, as City Council speaker, a member she considered a “slime ball.” De Blasio complied.

Asked whether she considered playing a less assertive role, McCray responded, “It’s not who I am . . . who Bill and I have been as a couple. . . . We’ve always been partners.” Clear and fair enough, but it raises two important questions. Are married government co-chief executives a good thing? And what about this particular twosome?

The Clintons’ co-presidency, which McCray points to as exemplary, suggests the answer to the first is no. Hillary Clinton’s unelected co-stewardship of the country went badly, both procedurally and substantively. Constant criticism and suspicion surrounded her de facto appointment of many top Clinton administration officials. Reverberations from her Arkansas law practice burdened the administration throughout. She badly fumbled the job formally entrusted to her in the first week of her husband’s presidency: heading the Task Force on National Healthcare Reform. Then there were the distractions of “Travelgate” and “Whitewater.”

McCray describes herself as a poet, not a politically connected lawyer. So she will arrive at Gracie Mansion with far less career baggage than Hillary Clinton brought to the White House. But the certainty of her centrality in a de Blasio administration makes her views very important. One view is that she doesn’t much like the 12 Bloomberg years nor, apparently, Mayor Michael Bloomberg himself.

During Bloomberg’s tenure, violent crime and especially murder rates steadily plummeted. New York City experienced a construction boom of unprecedented scope. Public schools and school choice improved. The long-neglected outer boroughs — especially Brooklyn, where de Blasio and McCray raised their children, but even the Bronx — experienced a renaissance. The whole city is safer, healthier and boasts an economy that weathered the deep recession far better than the state and nation.

Although many lifelong city residents see hope and progress in the resurrection of once drug-infested neighborhoods — such as Manhattan’s Alphabet City, and Greenpoint, Brooklyn — McCray bemoans that “we are losing our communities.” She points to “progressive capitals” such as Cleveland “doing exciting new things.” According to McCray, Bloomberg bears much of the blame for the Big Apple falling behind such places: “Our leader was a billionaire, I think it contributed to it.”

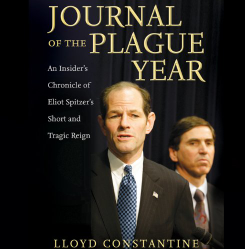

It is expected — and not necessarily bad — that spouses exert influence behind the scenes while publicly performing useful work. In recent years, the role of first spouse has expanded. One of the minor tragedies of the Eliot Spitzer gubernatorial fiasco, which I was part of as the governor’s senior policy adviser, was that Silda Wall Spitzer didn’t get to finish the great work she had skillfully begun on children’s nutrition, health and education. But a distinction must be made between the elected official and the spouse. The Clinton legacy includes a cautionary tale demonstrating that governance, already difficult, can become much more so when that distinction is blurred or ignored.

I voted for Bill de Blasio — and Bill de Blasio only. I didn’t sign up for a duo. And I’m certainly not interested in an unelected co-mayor who comes in despairing over the amazing progress my city has made over the past dozen years.

0 Comments