Looking to make a political comeback, Eliot Spitzer chose the wrong race and the wrong time

On Sept. 10, Eliot Spitzer, one of the most powerful state attorney generals in memory, whose name once frequently came up when talk turned to potential presidents, lost the Democratic primary for New York City comptroller to Scott Stringer, a Manhattan borough president so undistinguished that I, a lifelong resident of Manhattan, cannot associate it with any achievement or failure or indeed anything at all.

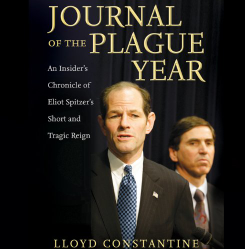

How did this happen? Most New Yorkers think they know — the world famous Sheriff of Wall Street rode his horse into the Executive Chamber, got tangled up with prostitutes, resigned in disgrace and tried to get back on the horse before the voters were willing to forgive and forget. That explanation while valid is only part of the truth.

There were other elements to his defeat, some within, some beyond Spitzer’s control.

He entered the primary too late to explain why he deserved a job he really didn’t want. And the three New York City daily newspapers, that rarely agree, even about the weather or movie times, engaged in a relentless campaign to defeat the man who had broken their hearts as much as ours. The New York Times, Daily News and New York Post had all endorsed Spitzer’s successful 1998, 2002 and 2006 candidacies for attorney general and governor. Indeed, the Post and News endorsed him in 1994 when he first ran and finished fourth in the primary for AG. They saw enormous potential in the young prosecutor.

After Spitzer entered the comptroller race, barely eight weeks before primary day, the tabloids pounded him daily, focusing on prostitutes, his wealth, marital discord, and such questions as whether he was dating. The Post ran at least one anti-Spitzer piece every day and an unflattering photo of him graced its front page more than a dozen times in the short, nasty and brutish campaign. The far more important mayoral primary took a back seat to pummeling Spitzer.

The conduct of the Times was out of character. Its stream of negative stories about Spitzer were nearly as gossipy as the Post’s, though they pretended to be policy oriented. The apex of this onslaught appeared on the front page of the Sunday Times on Aug. 18, with the headline “Stringer Gets Endorsements of Three City Newspapers” sitting atop a column that began “Three major daily newspapers in New York City made it bluntly clear this weekend whom they did not want to see as the next comptroller: Eliot Spitzer.” This “news” vied for prominence with U.N. teams’ arrival in Syria to investigate reports of chemical weapons.

As Spitzer had destroyed his governorship, five years later he handed the press the weapons to make his campaign most vulnerable to their attack. He wanted to be mayor not comptroller. Had he timely entered the primary for the top spot, he would have had a chance to redefine himself and explain to voters why now unencumbered by an illicit sex life he was ready to be the great executive that a record majority had sent to Albany.

In this respect, the cartoonish mayoral campaign of former Congressman Anthony Weiner proved instructive. Weiner, far less famous and accomplished than Spitzer, out of office comparatively briefly and whose sins exceeded Spitzer’s as measured on the “yuck meter,” quickly shot to the top of the polls. Weiner was brought down only by a second wave of recent sexting revelations.

In Spitzer’s five years out of office, he apparently walked the straight and narrow, appeared frequently, and for almost two years daily, on national TV as a brilliant commentator on issues that must be mastered by the mayor of the world’s financial, cultural and information capital. A full year’s campaign for the job he really wanted would have allowed Spitzer to give voters information to contrast with the daily assault of the city’s newspapers. And though the attacks from the Post and Daily News would not have been much different, the Times’ attitude might have been. Its editorial board saw the comptroller gambit for what it was, an opportunity for Spitzer to regularly score points at the expense of a new mayor. But had Spitzer run for the top job, he would have faced a field of candidates who appear small and weak compared with their larger-than-life predecessors, Mike Bloomberg and Rudy Giuliani, and with Spitzer. The Times could well have concluded that the only candidate of mayoral stature was Spitzer.

With all that going against him, Spitzer’s wife Silda shunned the campaign, a powerful signal to women voters to do the same. That sealed Spitzer’s fate, and with hindsight should have told him to enter the right race earlier or wait for a better one down the road. Spitzer, still young and strong, has his health, money, experience and enormous intellect intact. There may still be a next and great chapter for the former governor. And though I voted for him, it was probably best for us and him that this gambit didn’t work out.

0 Comments